When are Bluefin near the surface?

Key points

- The vertical structure of the water affects how much time Bluefin spend near the surface.

- Stratified water has a warm upper layer, with a strong temperature gradient (or thermocline) between the warm layer and the cold water below.

- In weakly stratified water, Bluefin tend to dive less frequently, but they dive deeper than 100 metres, and stay for long periods at depth. Bluefin spend less time in the upper 10 m.

- In strongly stratified water, Bluefin dive frequently to much shallower depths (less than 100 metres), and stay for shorter periods at depth. Bluefin spend more time in the upper 10 metres.

- When there is a stable warm, surface layer creating stronly stratified conditions, the tuna will frequently dive through the thermocline to feed, but they also return to the surface more often, and spend more time in the upper 10 metres.

- Bluefin are more accessible to trolling when they are in the surface waters, so the implication is that fishing should be better when the water is strongly stratified after sunny, calm conditions.

Details

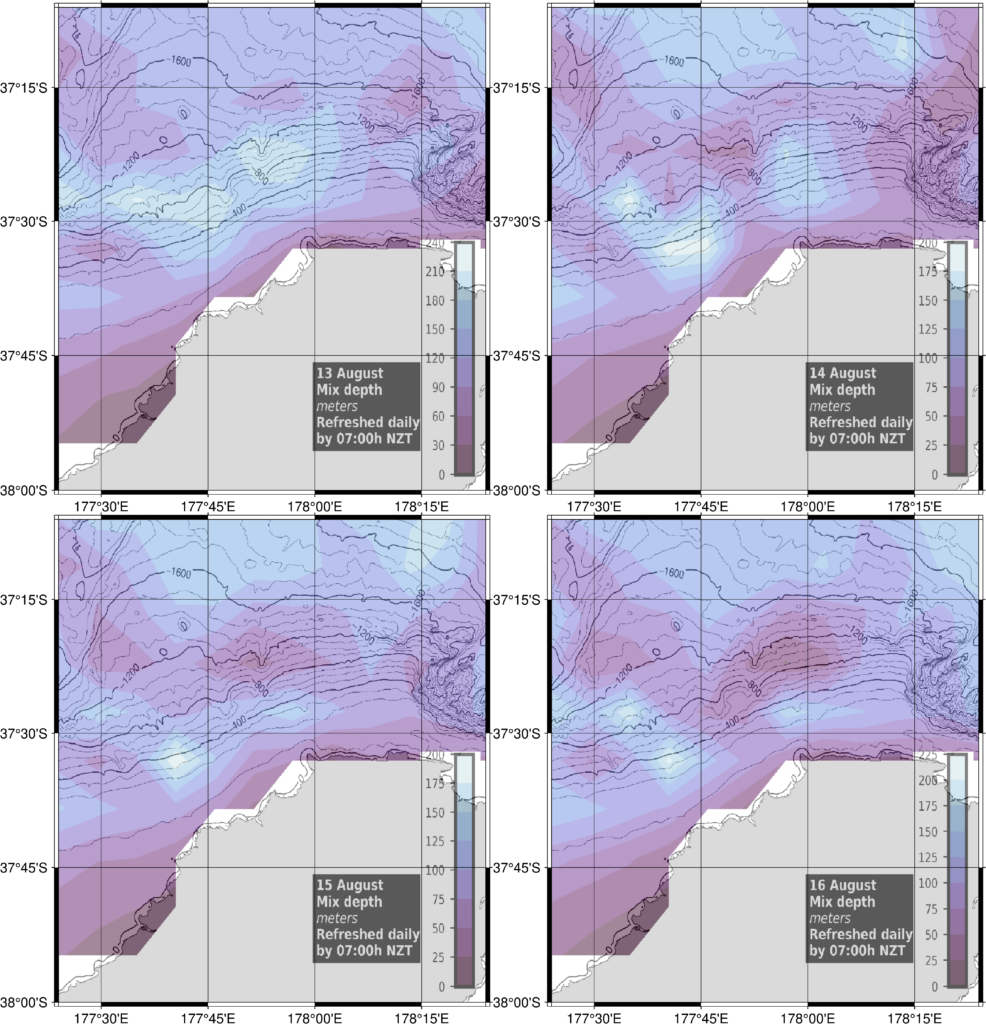

The vertical structure of the upper ocean has a big effect on the productivity and distribution of plankton near the surface of the ocean. The vertical structure also affects the concentration of feed, and that affects the behaviour of Bluefin. Vertical structure of the water is controlled by the interaction of heating by the sun, wind-driven mixing, and the density of the water. In offshore areas, or in areas away from river outflows, density is determined mainly by water temperature. The sun warms the surface of the ocean, and the wind blowing over the ocean distributes the heat by mixing the water.

As the sun warms the surface water it becomes less dense and forms a cap sitting on top of the cold deeper water. The temperature changes rapidly at the boundary between the warm less dense surface water and the denser, cooler water below. This boundary is called the thermocline. If you have ever swum in a lake in the summer and found it warm as bathwater in the surface, but freezing cold when you dropped your feet down, you have experienced the effect of a thermocline.

When there is a warm cap on the ocean, the water is said to be stratified (or layered). If the wind has been calm, and the weather sunny, the warm surface layer will be stable, and strongly stratified conditions may develop. In these conditions, Bluefin dive frequently to relatively shallow depths (less than 100 metres). They dive rapidly, feed below the thermocline and return to the surface waters frequently, spending as much as 65% of their time in the upper 10 metres.

If the wind rises, and continues to blow, the warm stratified layer will mix, and the thermocline will erode, reducing the temperature gradient. The wind mixing will create weakly stratified conditions. In this better mixed water, Bluefin dive deeper to depths greater than 100 metres, and stay longer at depth, spending less time in the upper 10 metres.

Concentrations of feed often occur just below the thermocline. These layers can be seen on an echosounder. Bluefin dive down through the thermocline to feed on these layers. When the water is strongly stratified, the Bluefin dive more frequently to feed. They also dive faster, and stay less time in the deep cold water than they do when the water is well mixed.

Bluefin use this foraging strategy during both day and night. These fish maintain a body temperature warmer than the water, so they remain highly efficient swimmers in cold water. Tagging studies have measured their internal body temperature and diving behaviour. These studies show that Bluefin body temperatures get warmer after diving, and this is caused by feeding at depth. The difference between their body temperature and the water temperature slowly declines as they spend time in the cold water, but is offset by the warmth gained by feeding. When the Bluefin return to the warm surface water, their internal temperature rises rapidly again, heating up their muscles.

The bottom line for fishers is that you can expect the Bluefin to spend less time at the surface when the water is well mixed or weakly stratified because they are foraging at depth for long periods. When there is a stable warm, surface layer creating strongly stratified conditions, the tuna will frequently dive through the thermocline to feed, but they also return to the surface more often, and spend more time in the upper 10 metres. Bluefin are more accessible to trolling when they are in the surface waters, so the implication is that fishing should be better when the water is strongly stratified after sunny, calm conditions.